Infrastructure is big business. Notwithstanding the $1.2 trillion that was approved by the U.S. last year, it has always been a sector that involves large figures. Recent statistics show that in 2023, the North American market size of infrastructure construction was in the region of $371 billion with this figure expected to rise to over $500 billion by 2025. Clearly, when it comes to building and maintaining our roads, pipes and cables, the future is looking bright. However, there are gaps in this network. While much money is spent developing infrastructure networks across North America that are fit for purpose, nothing is ever truly perfect. Rail, road and pedestrian networks are being overhauled through massive tranches of public funding giving residents services that meet the needs of modern society. However, elements of our communities can be left isolated, unable to access the services required for independent living.

Infrastructure is supposed to be the great leveller. It is the foundation upon which every community can thrive and develop. With a well-run and fully equipped infrastructure network, every citizen has an equal chance at building a successful life. Unfortunately, barriers to access remain. The full potential of infrastructure projects is often left unrealized. In the absence of minority groups and marginalized communities in the decision making process, inequalities can be exasperated by the design and management of infrastructure networks. Take travel as an example. As anyone who has visited a foreign city can attest to, navigating a space can be challenging. For those with sight loss or impaired vision, these challenges can be insurmountable.

There are, however, growing numbers of organizations, companies and individuals that are advocating for these groups by designing inclusive technology. Ambitious inclusive infrastructure is being designed with the goal of allowing all users to maximize their participation and engagement in the world around them. A global business consultant explains how infrastructure planners can unintentionally exclude people through design flaws. “Underdeveloped and gender-blind infrastructure often hinders women and girls from accessing basic services to support their upward social mobility and reduce gender inequality. Infrastructure can also discriminate based on age – in many areas, barriers to physical access prevent the very young and the elderly from benefiting from infrastructure. Race, ethnicity, caste, and other social categories may exclude certain groups from the benefits of developments, especially if their communities are based in informal settings. Moreover, disability inclusion is not consistently and effectively embedded within the infrastructure sector, and as a concept is still not comprehensively understood in many low-income countries.”

This need to create more inclusively-minded infrastructure networks is not merely a financial or local consideration. Many international conventions, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) stipulate access to infrastructure as a key component. Additionally, the G20 has had a long-standing focus on social inclusion and how it links to the design of quality infrastructure networks.

NaviLens is a tech company based in Murcia, Spain. It has developed an infrastructure collaborating app that uses haptic and audio supports to assist navigators to safely make their journeys. The app detects images —similar to QR codes— without using GPS or requiring access to wifi or bluetooth. NaviLens explains that these codes can be read almost instantaneously and at a great distance, making it ideal for navigating. This technology is highly efficient and inclusive in many ways. It is the fastest such reader available and can scan multiple tags simultaneously, making it highly communicable to the end user. TransLink, the Metro operator in Vancouver recently trialled the technology to great success. According to Thor Diakow, spokesperson for TransLink, the trial was a high priority. “Despite it being not a huge percentage of our ridership, it’s very important to make sure that we provide accessibility for people experiencing partial or full sight loss.”

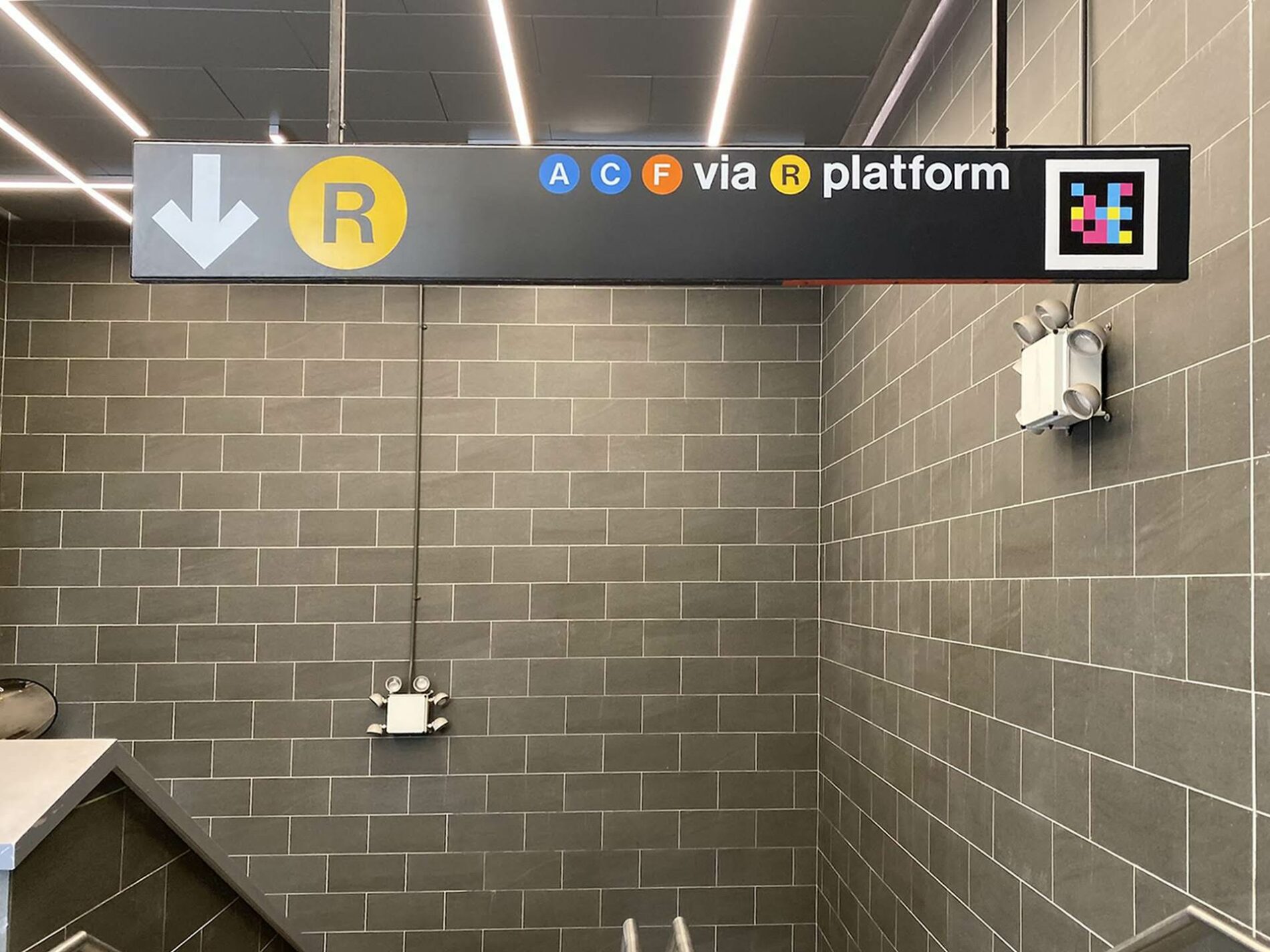

NaviLens has also launched its colourful codes on the New York Metro. This bustling rail network could potentially be an impossible task for a person with a visual impairment. However, by accessing one of over one hundred codes, users can be more independent in unknown spaces, can be guided indoors through an innovative Augmented Reality experience without the need for GPS or bluetooth and receive real-time train arrival information.

Photo by NaviLens

Photo by NaviLens

The company has not stopped at transport, either. Over thirty household shopping brands including Gillette, Pantene, Olay and Kellogg’s are now using NaviLens codes to assist shoppers in finding the necessary products. Most recently, Coca-Cola rolled out NaviLens codes across its Christmas can multipacks, which can be scanned from distances of up to four metres to help blind and partially sighted consumers.

AT2030 is an organization that seeks to improve access to Assistive Technology (AT). Led by Global Disability Innovation Hub and funded by UK Aid, is hosted a panel discussion at Cop28 titled ‘Inclusive Infrastructure, Disability and Climate Change: what’s needed to leave no one behind.’ According to those at AT2030, the purpose of the discussion is manifold. “For disadvantaged groups, the accessibility of the built environment, infrastructure and cities is vital to ensure full participation in daily life. Evidence shows that persons with disabilities are worse impacted by the effects of the climate crisis but remain excluded from urban development processes and climate action. Organizations around the world are already working to bridge this gap, and this event will share what’s being done and what’s next, outlining priority actions for disability-inclusive climate infrastructure and looking at how and why people do not have equitable experiences of the world around them.”

Around the world, barriers to access and inclusion are an unfortunate aspect of life. While much is being done to overcome these challenges, there is much work to be done. For many individuals, navigation, accessing community resources and living their daily lives is severely impacted by the way our infrastructure networks are planned and built. A recent survey by Infrastructure & Cities for Economic Development (ICED) demonstrated just how vital this is. “Well planned infrastructure and inclusive urban services are fundamental to unlocking the potential of people with disabilities. Currently, Disability Inclusion (DI) is not consistently addressed across infrastructure programming and policy dialogue. It is not always clear to DFID staff or partners what DI means in relation to infrastructure and growth, and the actions they might take to achieve it. This is coupled with a perception that addressing disability in infrastructure programming is prohibitively expensive and often unaffordable within project or programme budgets.”