In the modern world of construction, building materials are no longer a passive element of the process. From beams and cabling to cement and wood, everything on a jobsite is scrutinized. Materials are now analyzed on any number of factors, from cost and availability to their environmental profile. Nothing is ignored. As businesses around the world experience ongoing supply issues post-COVID, experts from across the industry are continuously searching for that elusive material. Versatility, strength, and price, while also being made from a sustainable source? Sounds easy.

With this in mind, it is no surprise that the industry has started looking towards plants and natural resources. By their very nature, the materials sourced from the earth are both strong and abundant. Furthermore, in many cases they cost almost nothing. In something of a perfect storm, materials are sometimes harvested from crops or plants that are otherwise useless. From Mexican seaweed to quick growing grass, the construction industry is now awash with alternative sources of materials. Next in line, however, could be the troublesome Southern weeds – Kudzu.

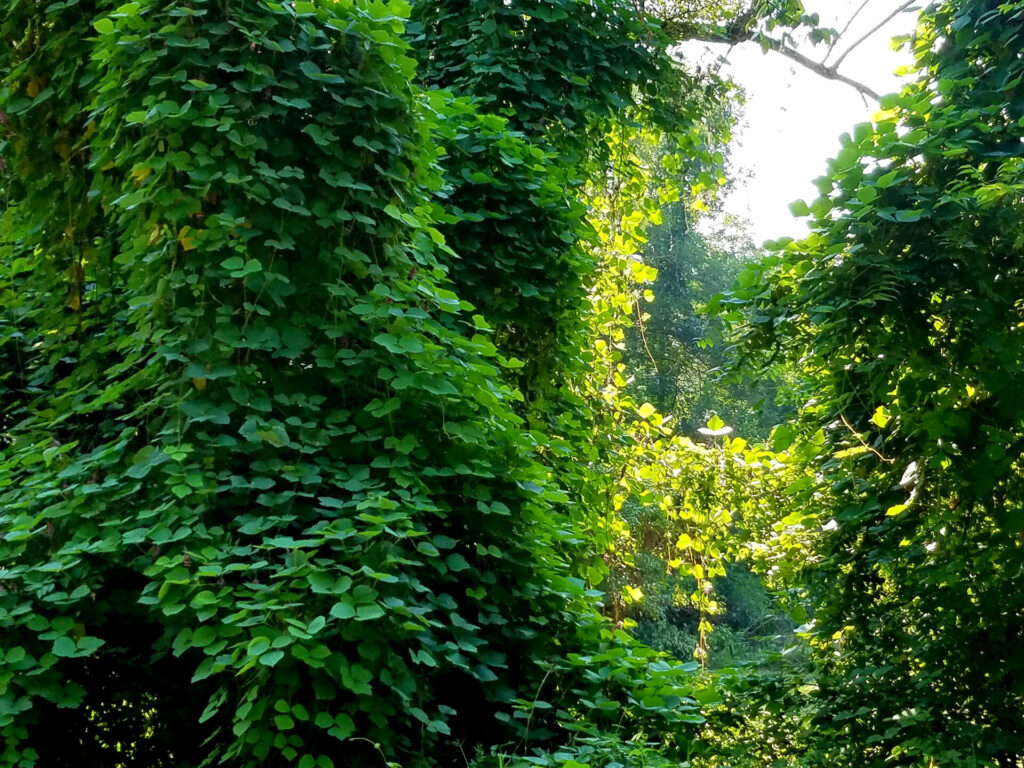

Kudzu was first brought to America in 1876 for the Philadelphia Centennial Expo. An ornamental plant with sweet smelling flowers, it grew popular as both a forage crop and a solution to soil erosion. However, things didn’t continue so positively. Finding a home in the Southeast region of the U.S., the leafy vines have thrived in the hot and humid environment. In an area where warm summer temperatures regularly hit 80 degrees Fahrenheit, Kudzu has spread wildly. Having subsequently been declared a pest weed in 1953 due to its invasive nature, it is safe to say that the growing didn’t stop in Philly. Rather alarmingly, Kudzu grows around a foot per day and can cover around 150,000 acres annually which, for the people of Tennessee and its surrounding states, is a significant problem. In 2020, results from a survey conducted by Oklahoma State University and Paulina Hannon, showed that the vine could result in a loss of $167.9 million and impact almost 800 jobs in Oklahoma alone. Harron, an environmental scientist at engineering firm AECOM, explained the level of threat it poses. “I think these economic impacts definitely serve as an incentive for governments, at different levels, to look into control strategies.” At last count, the plant covers almost 8 million acres of land in Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, Florida, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Mississippi.

So, where does the construction industry fit in and what are these control strategies? Given that it is a hard, fibrous material, advocates of Kudzu believe that it is tough, flexible, and perfect as a building material. When Katie MacDonald and Kyle Schumann began to explore the possibilities of using the plant in construction, they had no idea where it would take them. “It’s hard to avoid it, and you see it blanketing just about everything. It becomes a real presence in the landscape. Kudzu is kind of the poster child of invasive plant species. To us, there seems to be an opportunity space where we might be able to incentivize something that’s good for the environment, like remediation, by making it a useful act of building material.” In 2012, the pair started After Architecture, an architectural studio with the goal of repurposing invasive species as construction materials both as a response to the problematic plants and the pre-existing challenges of sustainable construction. For MacDonald and Schumann, Kudzu is the perfect choice. “We were thinking about the hardiness. It’s really a persistent material — that’s what made it such a challenging invasive species. It’s really hard to cut away, it rolls so fast, it entangles itself with things,” said MacDonald. “We used it as basically fibrous and loose wall assembly, and it was kind of similar to the idea of OSB (oriented strand board) which is a really standard building material.”

As After Architecture continue to explore the possibilities of Kudzu in construction, its founders are busily educating the industry. Models and examples of its efficacy are being produced by the company and many are raising eyebrows. One such example are the walls of an architectural installation called Homegrown. The structures walls were built with Kudzu and Bamboo and formed into panels using a bio-based binding agent. For After Architecture, the result is shared somewhere between traditional and the hyper-modern. “The development of a reusable, inflatable mold was driven by environmental concern and the desire to transition away from traditional subtractive methods for producing irregular molds, which are often cut from large disposable foam blocks. Using a hybrid workflow, wall designs were modeled digitally and then constructed physically using the novel pneumatic mold. Created using novel technology but physically composed of plant fibers, the installation is simultaneously primitive and high-tech.”

“Created using novel technology but physically composed of plant fibers, the installation is simultaneously primitive and high-tech.”

With the body of research growing steadily around the positive uses of this pest weed, it seems as though the tide may be changing. Kudzu is showing potential in areas as diverse as biodegradable food packaging, livestock feed, art, and cuisine. In fact, a short distance from Tennessee is Asheville, where regular meetings take place exploring and educating attendees on cooking and medicinal uses for Kudzu. However, for MacDonald and Schumann, their vine walls are not the end of the road. The pair are determined to harness the unlikely power of invasive species for the benefit of the construction industry. Their experiments and modelling have made the industry sit up and take note. After Architecture have amassed a number of awards and prizes for their research and design work, such as the 2022 Architecture R&D Award and most recently the Architectural League Prize winners for 2023. For After Architecture however, accolades are a happy by-product of the company’s work. For them, the work is demonstratable, rather than commercial. Rather than bring materials to the market, the company is bringing questions. Models and installations are triggering conversation in an environment that has been a closed shop for too long. In 1876, the sole purpose of Kudzu was to appeal to distinguished guests. Having become a thorn in the side of many, its popularity had most certainly peaked. Now however, with the aim of using a wide range of invasive plants as the stimulus for a deeper conversation around sustainability, it looks as though Kudzu is regaining some of that start quality. For After Architecture, it is just the beginning. “This area is still emerging, and there is much work to be done. A key focus is thus to identify the spatial potentials of these new material systems. Much of our work advancing biomaterial construction takes form as material prototypes and pavilions. These small-scale investigations and temporary installations can sometimes feel like demonstrations free from the constraints of permanent construction and habitation: parlor tricks.”